Bivouac of the Dead

Although stanzas from Theodore O'Hara's elegiac poem, "Bivouac of the Dead," are inscribed on iron tablets found throughout some of the oldest units of this country's national cemeteries, there is little public recognition of this poet-soldier and his long-lived literary contribution to the memorialization of fallen troops. O'Hara's military service bridged the period from the Mexican War, whose action inspired the poem, to the Civil War, which led him to places where some of the first cemeteries were created. An elegy, or elegiac poem, expresses feelings of melancholy, sorrow or lamentation—especially for a person or persons who are dead. It may seem unusual that verse written about heroes of the relatively remote Mexican conflict was appropriated for the Civil War more than a decade later, but "Bivouac" had captivated the attention of a patriotic nation and would continue to do so for decades to come. Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs (1816–1892) recognized its solemn appeal and directed that lines from "Bivouac" grace the entrance to Arlington National Cemetery.

The Poet

O'Hara was probably born in Frankfort, Kentucky, on February 11, 1820, where his Irish Catholic family lived. Comfortable and able with academic study, his education was punctuated by accolades for his writing and oratory skills, which prompted O'Hara to study law. By 1845 he was employed at the U.S. Treasury in the nation's capital.

As a captain promoted to brevet-major, he saw combat in the Mexican War (1846–1848), including the Battle of Buena Vista. He served again in the conflict with Cuba (1850–1851) until suffering an injury at the Battle of Cardenas. For the next decade O'Hara's career returned to one of words, and he served as editor of the Mobile Register, Louisville Times, and Frankfort Yeoman, sequentially.

Volunteering for active duty again in the Civil War, O'Hara served in the Confederate Army as a colonel in command of the 12th Alabama regiment, and subsequently saw action at Shiloh and Stones River in Tennessee. After the war he briefly took up residence in the vicinity of Guerrytown (Barbour County), AL, but he soon fell ill and died on June 6, 1867. Described as a handsome bachelor, O'Hara spent his life traveling from place to place and never owned a home. This itinerant lifestyle of journalist and soldier may have masked frequent bouts with depression and an addiction to alcohol, according to some accounts. Upon his death at age 47, O'Hara's body was initially buried in Columbus, GA.

Although O'Hara wrote "Bivouac" as a remembrance of the many casualties suffered by the Second Kentucky Regiment of Foot Volunteers who fought at the Battle of Buena Vista, the verse was produced as part of the dedication ceremony for a monument erected to these men long after the confrontation. The battle of February 22–23, 1847, saw 4,759 Americans under the command of General Zachary Taylor repulse an estimated force of 18,000 Mexicans led by President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. More Americans fell at Buena Vista—267 killed and 456 wounded—than any other battle in the war, which concluded with the United States compensating Mexico for the ceded Texas, and New Mexico and California becoming U.S. territories.

The fallen American officers were buried in the state cemetery at Frankfort, KY, on July 20, 1847, at the behest of an eager public and state legislature that pushed for their reinterment in native soil. This gathering was reportedly attended by 20,000 persons, but it did not include O'Hara, as he did not return to the city until fall 1848. That same year, the Kentucky legislature appropriated $15,000 for a military monument in the state cemetery, to be inscribed with the names of significant battles and the citizens who fell in them. The banded Italian marble shaft was erected in 1850. Although it is wishful history that O'Hara may have read "Bivouac" as part of the dedication of the military memorial, this has not been documented. He did, however, read the poem four years later as part of a eulogy for the reinterment of Major William T. Barry and General Charles Scott in the same cemetery.

While O'Hara was editor of the Mobile Register in 1858, "Bivouac" was published in that newspaper in what is considered the original form; two years later it appeared in the Louisville Courier with the explanatory introduction: "Lines written at the tomb of the Kentuckians who fell at Buena Vista, buried in the cemetery at Frankfort." O'Hara apparently changed words throughout the verse quite frequently, and different versions of it appeared at different times. He removed the names of specific locations, for instance, to elevate the work as a more pure elegy. The single-largest change shortened the poem from 12 stanzas to nine stanzas by omitting the sixth, seventh, and eighth stanzas, and reconstructing the fifth one. The shortened variation is the one used by Ranck (1936), with the approval of the poet's sister, but the original longer version is the one found in Holt (1992), A Promise Made (2000), and it is the one most often cited today.

Pursuant to a resolution by the Kentucky legislation aimed at returning the "ashes of her brave," O'Hara's body was removed from Georgia to the "state military lot" in his home of Frankfort, and on September 15, 1874, was reinterred there along with the remains of fellow officers from the Mexican War. His grave is marked by a tablet bearing the relief of a sword and scabbard encircled by a wreath of oak and laurel, appropriately located at the base of the Kentucky military monument of 1850. The reinterment included a reading of "Bivouac of the Dead" by Maj. Henry T. Stanton, a friend of the poet-soldier who observed, "O'Hara, in giving utterance to this song, became at once the builder of his own monument and the author of his own epitaph."

"Bivouac" in the National Cemeteries

Before "Bivouac" found its way into the designed landscapes of the national cemeteries, it may have had as its forebear crudely fabricated versions placed informally on the transitional landscape of the battlefield-turned-burial ground. According to one early O'Hara biographer, Kentucky historian George Ranck, "One stanza of it was inscribed upon a rude memorial nailed to a tree upon the battlefield of Chancellorville. Another was engraved upon a military monument at Boston, MA, and still another adorns a memorial column that marks the place where occurred one of the most bloody contests of the Crimean War."

By 1890, one visitor to a number of cemeteries observed: "Quotations from this one poem are repeated over and over, at the gateways and on painted boards at the turns of the avenues among the graves. In Antietam cemetery one might pick up and put together almost the entire production from these inscriptions."

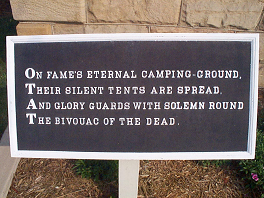

The most frequently quoted passage of "Bivouac" is the quatrain at the conclusion of the first stanza: "On Fame's eternal camping-ground/Their silent tents are spread/That Glory guards, with solemn round/The bivouac of the dead." Use of the verse on McClellan Gate at Arlington and other national cemeteries, may have been by order of Quartermaster General Meigs, who was responsible for construction related to national cemetery development, including the gates and superintendents' lodges.

The cast-iron tablets were fabricated at the War Department's Rock Island Arsenal, Illinois, in 1881–1882, "to take the place of notices, verses, etc., on painted signboards which had become unsightly and were too costly to renew as frequently as required."

Although many observers recognize the verse, the name of the poet is less familiar—and this may have been a deliberate obfuscation on the part of Meigs. The iron plaques provided to the national cemeteries do not credit any author for "Bivouac." The most logical explanation is that since O'Hara fought on the Confederate side, it would be unseemly to record his name in the cemeteries occupied by Union dead. The popularity of the verse, however, apparently led many visitors to inquire about the source of the poetry.

Similar anonymity is granted the portions of the verse appropriated for the title pages of eight of the 31 Roll of Honor (and subsequent "Disposition") issuances, although other period verse is similarly used without attribution.

Literary Significance

In contrast to the poem's anonymous expression in the national cemeteries, O'Hara was credited with its authorship over repeated appearances in the popular literature of the late 19th and 20th centuries. In 1875, Ranck described the limitless popularity of "Bivouac" nearly a quarter-century after it was written: "The hold of this elegy upon the popular heart grows stronger and more enduring. It is creeping into every scrap-book (sic); it is continually quoted upon public occasions."

The poem was a favorite in the press over the years, borne out by its inclusion in publications such as Littell's Living Age (1866), Library of Poetry and Song (Bryant, late 19th century), Our Children's Songs (Harpers), and The Century (1890), as well as finding its way onto Decoration Day post cards of the early 20th century.

One rare public disagreement with "Bivouac" is articulated in The Century magazine (1890) by writer Rossiter Johnson, who had political objections to the poem's origin because it celebrated "volunteer soldiers who had lost their lives in an unholy war, that with Mexico." Remarking that "a stroll through any of our national cemeteries will suggest the idea that the War Department has official knowledge of but one elegiac poem," he proposed that the government expand its literary references to more appropriate occasions and poets—many of whom fell in battle during the more righteous Civil War. Among his recommendations for alternative martial literature originating in the Civil War experience were: Henry Howard Brownell's "Bay Fight," Benjamin F. Taylor's "Cavalry Charge," Edmund Clarence Stedman's "Gettysburg," Reverend Samuel P. Merrill, "Dirge for a Soldier," as well as works by lesser-known poets such as Theodore P. Cook, Michael O'Connor.

"Bivouac of the Dead" is one of two great elegiac poems for which O'Hara is remembered, and in a literary context it has been compared to Thomas Gray's "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard," Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "Psalm of Life," William Collins' "How Sleep the Brave," and Charles Wolfe's "The Burial of John Moore." According to Ranck, O'Hara was America's first "elegiac poet of acknowledged genius."

The endurance of "Bivouac" through most of the 20th century is evidenced by its inclusion in anthologies and poetry collections: from 1920–1963, it was found in 24 such texts. By 1973, however, the number fell to just 16 literary collections, in keeping with changing attitudes about military honor and politics.

Today this verse is found on McClellan Gate, 1879, the original entrance to Arlington National Cemetery, and in Antietam National Cemetery. Although the cast-iron tablets were largely removed during the late 1920s and early 1930s, they are extant at 14 national cemeteries: Los Angeles, Wood, Rock Island, Mound City, Marion, Keokuk, Dayton, Hot Springs, Leavenworth, Togus, Grafton, Finn's Point, Cypress Hills, and Danville, IL.

In fall 2001, the National Cemetery Administration commenced an initiative to install a new cast-aluminum tablet featuring the first stanza of "Bivouac of the Dead" in all the existing national cemeteries where they are missing, as well as national cemeteries under development.

Sources

RG 92, Office of the Quartermaster General. Microfilm (M997), Annual Reports of the War Department, 1822–1907. National Archives and Records Administration.

Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs, Jr., and Thomas Clayton Ware. Theodore O'Hara: Poet Soldier of the Old South. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1998.

Hume, Maj. Edgar Erskine. Colonel Theodore O'Hara - Author of "Bivouac of the Dead". In southern Sketches No. 6, First Series, general editor J.D. Eggleston. Charlottesville, VA: Historical Publishing Co., 1936.

Holt, Dean. American Military Cemeteries: A Comprehensive Illustrated Guide to the Hallowed Grounds of the United States, Including Cemeteries Overseas. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1992.

Johnson, Rossiter. "Martial Epitaphs." The Century, a Popular Quarterly Vol. 40, No.1 (May 1890): 156-57.

Littell's Living Age. Fourth series, Vol. III (October-November-December 1866): 194.

Ranck, George W. O'Hara and His Elegies. Baltimore: Turnbull Brothers, 1875. This volume contains O'Hara's other major work, "The Old Pioneer," about Daniel Boone.

Strait, Newton A. Alphabetical List of Battles, 1754–1900: War of the Rebellion, Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection, and All Old Wars with Dates. Washington, D.C.: 1914.

U.S., War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General. Roll of Honor. 25 volumes. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, published 1868–1871. Reprinted in 10 volumes, Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1994.

Wilson, Robert Burns. "Theodore O'Hara." The Century, a Popular Quarterly Vol. 40, No.1 (May 1890): 106-10.